Each year many yachts leave the Canary Islands towards the end of November to arrive in the Caribbean after the hurricane season has ended and also to be able to get a full season of cruising before the start of the next one. Hurricane season runs from June to November although tropical storms can develop outside these dates.

Weather

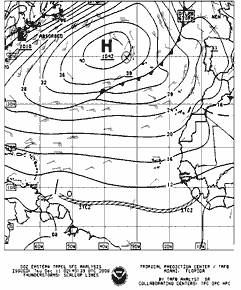

A typical synoptic chart for the crossing.

The tradewinds are driven by the position and intensity of the Azores High. This varies year on year and some years it is downwind the whole way across with yachts claiming a spinnaker run from start to finish. This is an exception rather than the rule and there is a great deal of inter-annual variability. November may be the most convenient time to cross, but it is not the most settled time of year to leave the Canaries and some years there may be a few days of headwinds before the tradewinds become settled.

When we study averages, pilot or routeing charts indicate a force 4 which is 11 to 16 knots but this is an average and would be considered a light wind year by many. At times 20-25 knots is experienced whilst occasionally yachts report a number of days with 25 to 30 knots and large seas.

In most years there is a region south of the Azores High that produces a good 18-23 knots, but it may take a dive south to the latitude of about St Lucia to find it.

Squalls

The frequency and severity of squalls do very year on year although we will see some on a trans Atlantic crossing. Sometimes they are individual squall clouds but at other times they will be organised in bands. We can expect a strong gust of wind as the squall hits along with torrential rain.

Tracking a squall

As squalls travel in the direction of wind higher up in the atmosphere, they do not exactly follow the surface wind. As a rule the squalls will come from a direction veered to the surface wind. Track them on radar or by using a hand-bearing compass. This implies that on a port gybe you will cross the track of the squall faster than on starboard, where your track and the squall’s track are likely to be similar. If the clouds are fast moving, raining and reach high into the sky, the gust front arrives with the rain and it will be strong – possibly to galeforce.

Route

“Go south until the butter melts then turn west,” or follow the rhumb line? Historically sailing ships would head south, almost to the Cape Verde Islands before heading west. Latitude was easy to measure, but longitude needed accurate time, so getting to the correct latitude then running the longitude down was an accepted method of navigation that also took advantage of the tradewinds. For a modern yacht, with good performance and good weather forecasting, considerable gains can be made by cutting the corner. On some years this is considerably faster, other years the traditional route is the best. It all depends how well established the Azores High.