About this page

How, why and when fog occurs.

Preamble

Every sailor fears fog in all its various forms. Given the choice, most sailors would probably prefer to be caught out in strong winds than a thick fog. At least with strong winds, given the sea room, you can heave-to. Caught out in fog there really is no safe haven. Even with radar, there are the ever-present worries of small vessels that give a weak echo and of larger ones that might not even see you at all. AIS is useful to “see” large ships but there is no guarantee that they are using it. Some quite large ships such as customs vessels or warships turn off the AIS for good reasons.

On this page -

What is the difference between Fog, mist and haze?

Fog, mist and cloud are all formed when air cools to its dew point (the term is self-explanatory). Water in the air may condense onto a cold surface such as the ground, a house roof or on to small particles in the air (known in the trade as condensation nuclei). At ground level the "cloud" is called fog or mist depending upon the visibility. At sea or for aircraft landing and taking off purposes, fog is defined as when the visibility is 1000 metres or less. Mist is a visibility between 1000 and 2000 metres. Normally, over land, forecasters use the word "fog" when the visibility is 200 metres or less. This is because a car driver may be fairly happy if he can see over 200 metres while the same is not true for an aircraft pilot landing at Heathrow or the skipper of a boat in mid Channel, particularly a small yacht.

Air can be cooled in several ways. First, the air can be lifted by flowing over a hill, by convection or by the convergence of two air streams. Secondly, it can be cooled by contact with a cold surface. It can also be cooled by raindrops in the air evaporating in the same way as when you hold a wet finger in a wind. Similarly, melting of falling snow will lead to cooling. Those with long memories from school will recognise these effects as being due to "latent" heat.

The term haze confuses some sailors. Haze is a reduction in visibility due to dust or smoke in the air. The differentiation from mist is because further cooling of the air when it is misty can lead to fog. With haze, that is not the case.

The two main types of fog

Most common over land is Radiation Fog which occurs on clear nights with light winds. Radiation from the ground escapes out to space, the ground cools and, in turn, cools the air in contact with it. On an absolutely still night, condensation will occur on the ground to form dew. With slight air movement, sufficient condensation forms on condensation nuclei to form very small droplets of water - mist or fog. If the wind increases or a layer of cloud comes over, then the fog is likely to clear.

Because Summer nights are fairly short, there may not be enough time for the cooling to create fog especially when the ground starts by being warm. From early Autumn through to late Spring, fog is always possible in such conditions.

Generally, radiation fog is not a sailing hazard except when it drifts out over coastal waters or down river valleys. Even then, the relative warmth of the water is likely to clear the fog.

The sailor is usually more concerned with Advection Fog caused by relatively warm, moist air flowing over a colder surface. Over land this is fairly rare except after a cold spell when the ground has become frozen or there is lying snow. A SW airstream will bring in warm air from the Atlantic. The cold ground cools this air and the result will be very poor visibilities even though the wind can be quite strong.

Over the sea, the same effect is quite common in some areas. This is when moist air flows across the sea towards colder waters; the cooling gives Advection Fog that we call Sea Fog. First, it is important to note that sea fog can occur at any time of day and with quite strong winds. With winds, over about F 4-5, the result may be low cloud and poor visibility rather than fog. In the English Channel, sea fog can occur at any time of the year but seems to be more common in the late Spring and early to mid-Summer when the water inshore is still fairly cold.

Around the East Coast of the UK sea fog is always possible when the wind is in the East. This is because the sea temperatures in the middle of the North Sea are always warmer than near the East Coast. This accounts for the persistent “haar” or “sea fret” that so often gives a miserable day near the coast while it is nice and sunny a little way inland. Around the Channel Isles, sea fog may be more likely in late Spring with a W wind. Later in the year it will also occur with an E wind. The water near the French coast gets warm in the Summer while the water around the islands stay comparatively cold.

Other forms of fog

Hill fog itself, obviously does not present a problem for yachtsmen. However, if it forms on fairly low coastal hills it can indicate that the air is near its dew point temperature and that sea fog may easily occur. When hearing reports of fog from the Channel Islands airports, it is worth remembering that these are on the tops of hills and may keep in fog for much of the day while at sea level the visibility may be not too bad, despite the low cloud.

Cooling occurs when rain falling through dry air evaporates. This might be sufficient to cause what is known as Frontal Fog. This is fairly rare. Not normally mentioned in the books is what I call Thunderstorm Fog. This can follow those thundery outbreaks that drift slowly up from Spain and France. Although the thunderstorms may have ceased, there can be a great deal of very damp air around and this all too easily can be cooled by the cold waters, say near the Channel Islands, to give very dense and persistent fog.

Another kind of fog, no doubt only of academic interest to most leisure sailors, is Arctic Sea Smoke. This results when very cold air flows from land to sea, perhaps round some fjords in the far north of Norway or Greenland. The relatively warm sea water evaporates quickly and is condensed by the cold air just as quickly.

How common is fog?

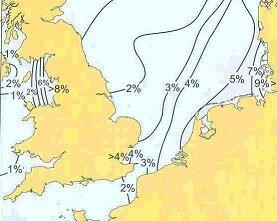

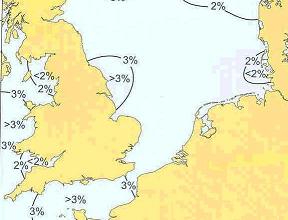

The figures below show significant differences between Summer and Winter in the frequency of fog over the seas around the British Isles.

Fog frequencies - JanuaryThe figure above shows the effect of the very cold seas near the Danish and German coasts in Winter while the middle of the North Sea stays relatively warm. Westerly winds are very likely to give fog. In the figure on the right, it is seen that fog is far less common over the eastern North Sea in Summer when the sea becomes warmer than in the central parts. In Summer, fog is more common near the UK east coast. Here, the sea stays cold compared to the central and eastern North Sea. Easterly winds are very likely to give mist or fog. |

Fog frequencies - JulyIn the English Channel, the higher frequencies of fog in July compared to January is probably a combination of factors. Stronger winds in January will lift the fog into low cloud. The higher sea temperatures near the French coast will lead to higher frequencies of fog in E winds than in the Winter. Thundery outbreaks will lead to patches of very moist air and some dense fog banks, |

Real-time sea temperature charts for the North sea are on Alisters page. For sea surface temperatures globally, go yo the World Sea Temperature site.

What advice for the sailor?

Around the UK, France and Spain the RYA Metmaps were very useful in that they gave average sea temperatures at their highest and lowest ie in February and September. These help you to see whether the air is coming from an area of warmer sea or not. Unfortunately, these Metmaps are no longer printed but are available from the RYA on-line. The chartlets above will also help. Remember that it is not just the local wind direction but the track of the air that is important. Has the air in the Channel really come from the SW? Is the air over the Channel Islands coming from the warm sea off the French coast?

As ever, monitor the forecasts but be aware that heavy rain and thunderstorms might make the air much moister than the forecasters realize. Keep a listening watch for warnings of fog, especially from the French weather service via CROSS. Unlike the UK, they do issue their Bulletins Météorologiques Spécials - BMS, for fog as well as for strong winds.

If it is at all possible, fit radar - but make sure that you know how to use it; radar assisted collisions, like GPS ones are not unknown! Remember that some large vessels such as wooden minesweepers and fishing boats may not show up.

Conventional wisdom for a small vessel is to seek shallow water where large vessels are unlikely to go. However, the use of Class B AIS may make it safer in an area where most ships can be seen on your AIS display and, hopefully, you will be seen on theirs. In shallow water, it is more likely that others do not have AIS transmitters. But, again, remember that nor will some large ones such as warships and customs cutters.

Moral – use all the tools at your disposal – including eyes, ears and common sense.